The Otago Deception: Was New Zealand’s Grand Railway Built on a Lie?

The Otago Railway Station mystery has puzzled historians and skeptics alike. Built in just three years (1903–1906) in Dunedin, New Zealand, this Gothic Revival masterpiece boasts intricate sandstone carvings, Belgian mosaics, and English stained glass. How did a small colonial city achieve this with only hand tools and horse carts? Dive into the evidence behind the Otago Railway Station mystery with Fabricated Foundations and uncover whether it’s a colonial triumph or a clue to a hidden, forgotten history.

The Official Narrative: A Miracle in Three Years

The history books are clear—or so they’d like you to think. The Otago Railway Station, a 725-foot-long Gothic Revival marvel, was designed in 1901, started in 1903, and finished by 1906, as detailed in official records. A three-year sprint to create:

- Ornate stonework carved from local sandstone and Oamaru limestone

- Intricate mosaic floors made with imported Belgian tiles

- Stained-glass windows shipped from England

- Iron latticework supporting a grand, vaulted interior

All this in a fledgling colony with a population of barely 750,000, limited railways, and no heavy machinery. Sounds ambitious, doesn’t it? Almost too ambitious. For a broader context, explore New Zealand’s colonial history.

The Timeline Problem: Too Fast, Too Perfect

Let’s do the math. From 1903 to 1906, colonial workers supposedly

- Quarried and transported thousands of tons of sandstone and limestone

- Crafted and shipped delicate mosaics and glass across oceans

- Assembled a precision-engineered structure with no electric tools or cranes

- Coordinated a workforce of skilled artisans in a region known for farmers and traders

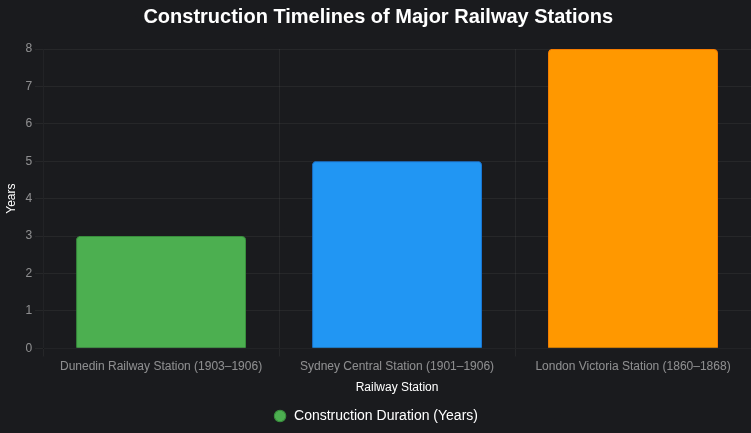

Three years. That’s 1,095 days to go from a blueprint to a fully functional, opulent railway hub. Compare that to similar projects:

- Sydney’s Central Station (1906): Took 5 years with better infrastructure.

- London’s Victoria Station (1860): Nearly a decade for comparable grandeur.

So how did Dunedin—a small port city in a remote colony—pull this off in half the time? Learn more about historical mysteries like this one.

Materials & Logistics: A Weighty Impossibility

Let’s talk about what it took to build this “Gingerbread House” of New Zealand:

- Sandstone & Limestone: The station’s facade and structure used local sandstone and Oamaru limestone. A single block of sandstone weighs ~2.2 tons per cubic meter. For a 725-foot building with towers and thick walls, we’re talking 5,000–8,000 tons of stone. Quarrying was done by hand, with dynamite and chisels. Transport? Horse carts over rough tracks from quarries 50–100 miles away. Moving one load could take days. Multiply that by thousands of blocks. Months, maybe years, just for stone.

- Belgian Mosaic Tiles: The iconic mosaic floors, with their intricate patterns, required thousands of tiles shipped from Europe. Each tile batch would take 3–6 months to manufacture, plus 2–3 months to sail from Belgium to Dunedin. Breakage was common—yet the floors are flawless. How did they manage zero defects with 1900s shipping?

- Stained-Glass Windows: Imported from England, these fragile masterpieces would need custom crates and months of careful transit. A single window could take 6 months to produce and ship. No cracks, no losses, no delays? In a port with no modern cranes?

- Total Weight Moved: Conservatively, 10,000–15,000 tons of materials, not counting interior fixtures like iron railings or marble counters.

Now, picture this: Dunedin in 1903. No forklifts. No trucks. No electric saws. Just horses, pulleys, and sweat. Moving and assembling this volume of material in three years would require a logistical miracle—or something else entirely.

The Tech Gap: Tools That Don’t Match

New Zealand in the early 1900s wasn’t an industrial powerhouse. It was a colonial outpost, focused on wool and gold, not architectural grandeur. The tech available included:

- Hand tools: Chisels, hammers, manual saws.

- Steam cranes: Rare, bulky, and rail-dependent.

- Horse carts: Slow, with a capacity of 1–2 tons per trip.

Yet the Otago Station boasts precision-cut stone, perfectly aligned mosaics, and fire-resistant ironwork. Compare it to other colonial buildings of the era—wooden shacks or simple brick depots. The jump in sophistication is staggering. Where did this expertise come from?

And then there’s the 1903 Dunedin Fire. A massive blaze tore through the city, destroying wooden buildings and parts of the railway infrastructure. Yet, somehow, the under-construction Otago Station—made of stone, steel, and glass—emerged unscathed. Was it luck? Or was it built with advanced fireproofing techniques not documented in the era’s records?

The Missing Records: A Paper Trail Gone Cold

Here’s where it gets murkier. The archives are oddly sparse:

- No construction photos: Not one clear image of the station being built.

- Missing labour rosters: Who were the workers? No detailed records of the skilled masons or artisans.

- Vague material logs: Partial receipts for stone, but no clear trail for tiles or glass.

In an era when newspapers celebrated every new bridge or warehouse, why is there so little fanfare about a project this grand? It’s as if the station appeared, fully formed, and the story was backfilled later.

The Inherited Hypothesis: A Relic, Not a Build

What if the Otago Railway Station wasn’t built in 1903–1906? What if it was uncovered—a pre-existing structure from a lost era, retrofitted to serve as a railway hub? Consider:

- Architectural Anomalies: The Gothic Revival style mirrors older, pre-colonial structures found globally, from European cathedrals to alleged Tartarian relics.

- Fire Resistance: The 1903 fire spared the station, suggesting materials or techniques beyond the era’s norms.

- Global Patterns: Like the Montsouris Reservoir or Palácio Monroe, the Otago Station’s timeline and tech don’t align with its context. Are we looking at another piece of a hidden, worldwide infrastructure? Explore more about New Zealand’s hidden past.

Could Dunedin’s pride be a remnant of a forgotten civilization, rebranded as a colonial achievement to hide its true origins?

Why Hide the Truth?

The Otago Railway Station still stands, a tourist attraction and a “heritage site.” But why are its origins so vague? Why no photos of the workers, no detailed blueprints? And why does its grandeur feel so out of place in a young colony?

Maybe the truth is too big. Maybe admitting the station predates 1903 would unravel the entire narrative of New Zealand’s history—and beyond.

The Otago Railway Station isn’t just a building. It’s a question mark—a challenge to the foundations of history itself. If they lied about this, what else are they hiding?

Call to Action

What do you think? Could a small colonial city have built this masterpiece in three years with hand tools? Or is the Otago Railway Station proof of a hidden past? Drop your thoughts in the comments, and let’s keep digging into the foundations they don’t want us to see.

🔗 Visit fabricatedfoundations.com | Uncover what they covered up

Post Comment